MRI can be used to examine almost every area of the body and is particularly well suited to particular tasks. Since an MRI is quite a complex investigation, simpler tests will often be used initially, such as radiographs or ultrasound studies.

Below are a few examples of common types of MRI examination:

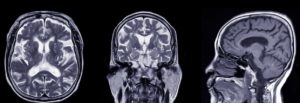

Brain and Spine

MRI scans are the most common method of imaging used for looking at the brain and spinal cord. Some of the principal conditions they can diagnoses in the brain and spinal cord are:

- Aneurysms of the cerebral vessels

- Strokes

- Tumours

- Multiple sclerosis

- Spinal canal narrowing

- Neurological disorders of brain and spine

- Traumatic brain injury

- Dementia

A specialist type of MRI called a functional MRI (fMRI) may be used to view the brain in action. An fMRI can be used to map brain activity and flow of blood in specific areas of the brain. This allows an accurate anatomical determination of which parts of the brain are carrying out essential functions, such as speech and movement. This can be an invaluable tool for some patients who may require brain surgery as it provides the surgeons with an understanding of an individual’s anatomy, including which side of the brain is undertaking important tasks such as speech and movement control.

Figure 2. Image through the spine. The arrow is indicating an area of image disturbance caused by the previous surgery.

Heart and blood vessels

MRI scans of the heart and blood vessels can evaluate:

- The thickness, movement, and health heart chambers

- Pumping capacity and efficiency of the heart

- Damage cause by previous heart attacks

- Structural abnormalities of the heart or great vessels

- Inflammation, blockages, or damage within blood vessels

Figure 3. Coronal view of the left ventricle and the aorta – one frame from a cine acquisition series used to assess function.

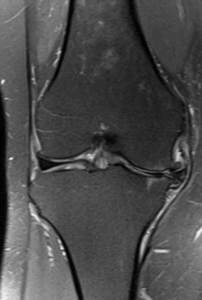

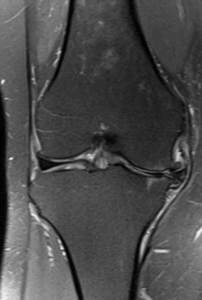

Bones, joints, and muscles

MRI scans can be used to assess:

- Problems with bones and joints, ligaments and muscles

- Infections of the musculoskeletal system

- Abnormalities caused by trauma or repetitive stress injuries

Figure 4. Image of the left knee viewed from the front showing damage to the medial part of the joint. This involves the cartilage disc in the joint, the articular cartilage lining of the joint and the bone.

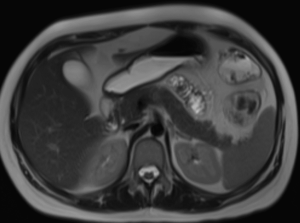

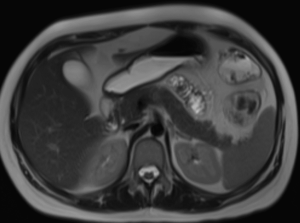

Internal organs

MRI scans can also be used to assess for abnormalities, pathologies, and tumours in many other internal organs, such as:

- Kidneys

- Liver

- Gallbladder and bile ducts

- Spleen

- Uterus

- Ovaries

- Pancreas

- Bladder

- Prostate

Figure 5. Image through the upper abdomen showing the liver, gall bladder, pancreas, spleen and kidneys.