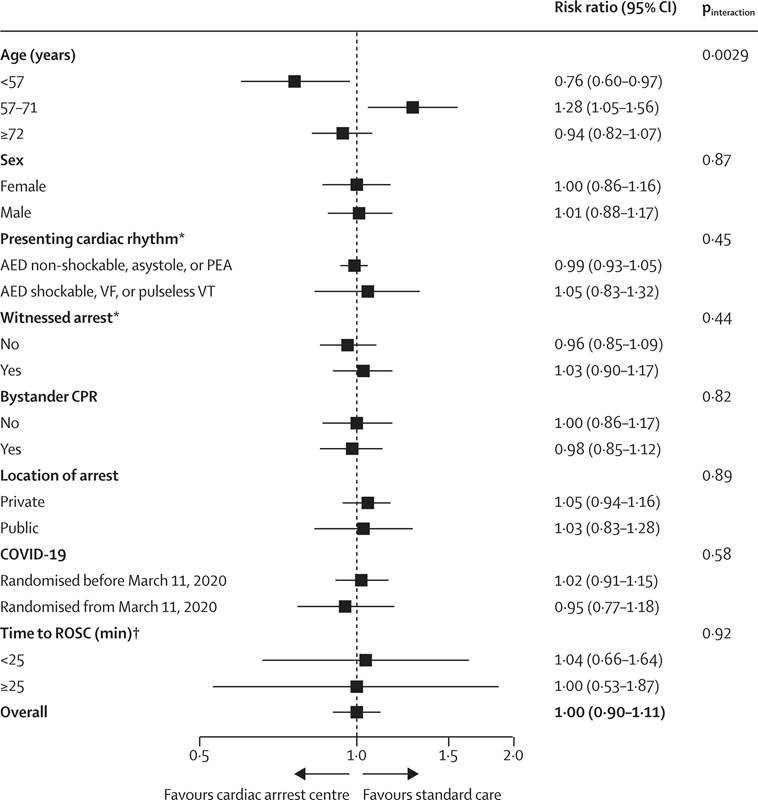

This trial looked at whether transporting to a major heart centre rather than the nearest A+E (ER) department would help the patient AFTER they had a return of a pulse.

These patients did NOT have an ECG that suggested a heart attack as the cause of the OOHCA- those patients still come to the Heart Attack Centers, such as the one Dr Malik helped set up and run at Hammersmith Hospital, London.

It did NOT seem to help to transfer such patients to specialist heart attack centres- BUT it also did no harm to do so. The transport time is longer, and unless there is a benefit, LAS might be better dropping the patient to a closer hospital, and getting to the next urgent case they need to help.

It seems that in the cardiac centre, more tests and diagnostics were carried out, e.g. angiograms, time on ITU, kidney support, etc., but it seems to not improve survival.

What is clear is how serious a condition it is. Even those that survived to hospital, had an over 60% chance of dying by 1 month. Thus prevention is much better than cure.